About the Idea

The idea to automate crawler creation came to me almost immediately after I started working as a software engineer. Many customers requested tools to extract data from old resources or public data sources for reuse on their sites. Each crawler creation was similar: first, explore the website layout, then write boilerplate code to get data from specific page parts. I wanted to optimize this process, but as an employee, I didn’t have time to write libraries and was expected to focus on customer projects. After some time, I changed jobs and programming language to C# with the ASP.NET Core platform (version 3). I wanted to improve my C# skills quickly, so I decided to implement a pet project using the new language. The old idea of simplifying crawler creation resurfaced. I looked at some websites and thought: “If someone could describe which blocks contain the required information, we wouldn't need to write code at all. The code could be generated automatically.”

First Concept

I decided to investigate whether it was possible to open web pages in a window and capture the selector of an element the user hovered over or clicked on. To test this theory, I created a minimal API that requested the entire page content of a specified URL. The application frontend requested the page entered by the user, and injected a JavaScript script that drew a red rectangle around a hovered element and logged clicks to the console. It worked on simple HTML sites, so I decided to start implementing the project.

First Implementation And Problems Encountered

After many iterations, I created the “web-crawler” project with the following concept:

- Users should create “crawler schemas” to describe how to extract data from a page using a comfortable interface.

- Then, the user should select which pages to extract data from. When the user first entered a page address, the loading of sitemaps began in the background. The intention was that once a crawling schema was created, “web-crawler” would know enough about the site's pages. The user could then select pages of interest using patterns.

- Once the schema was ready, the user could run the crawling process manually or set up a schedule.

- Results could be uploaded manually or sent via webhook in CSV or JSON format.

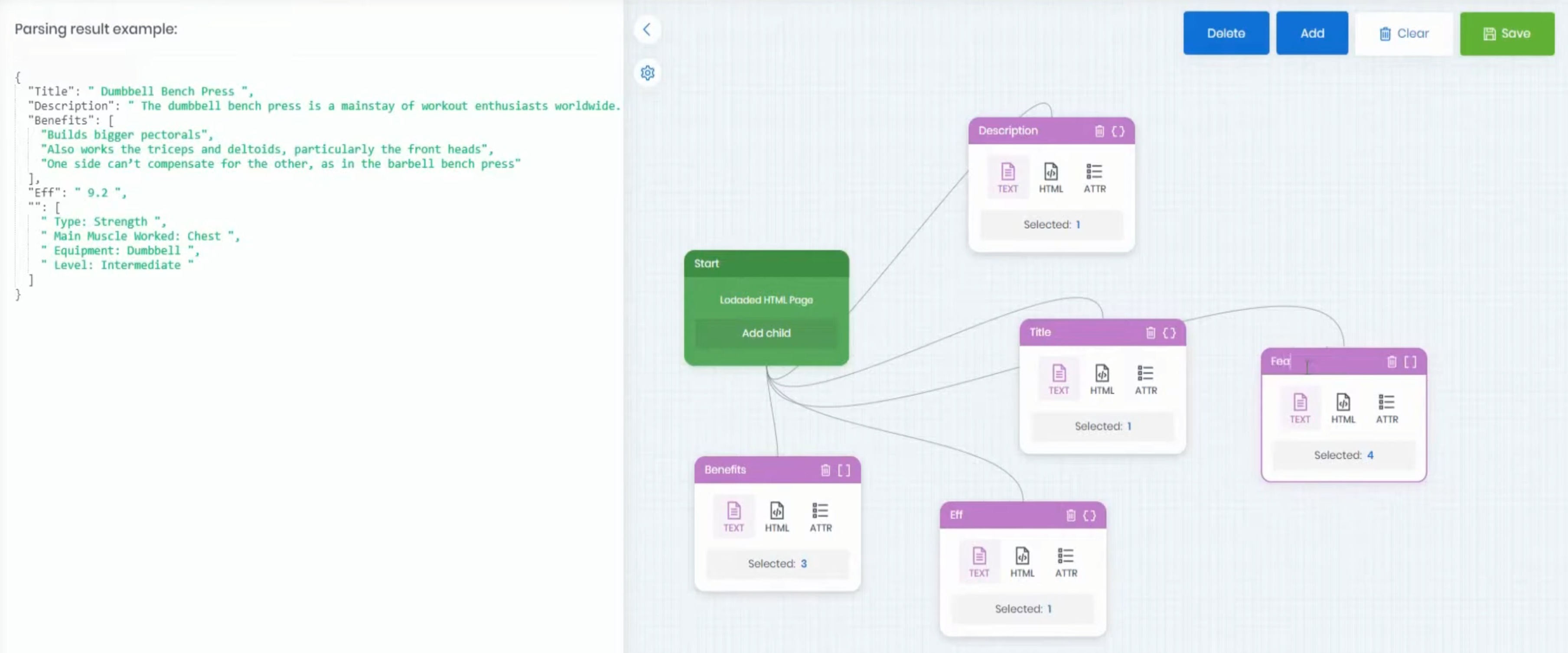

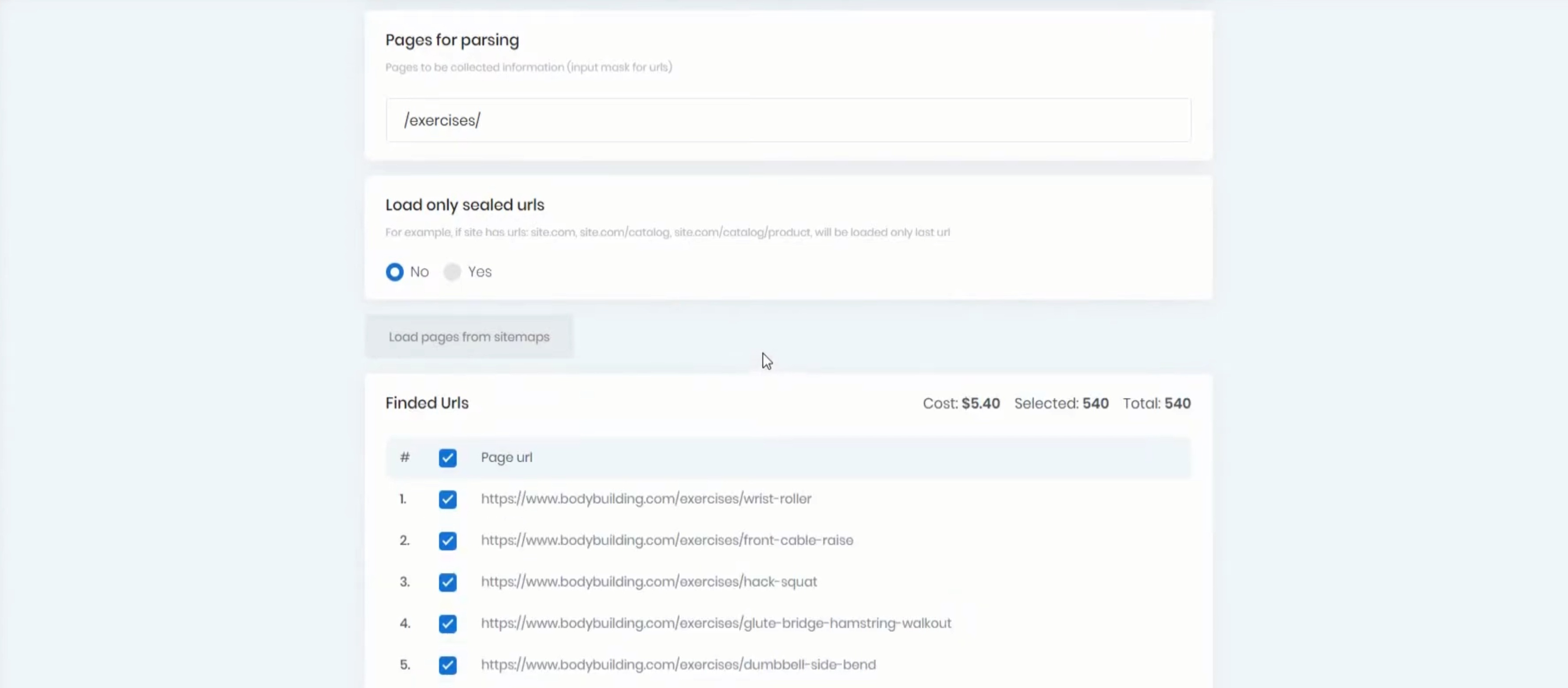

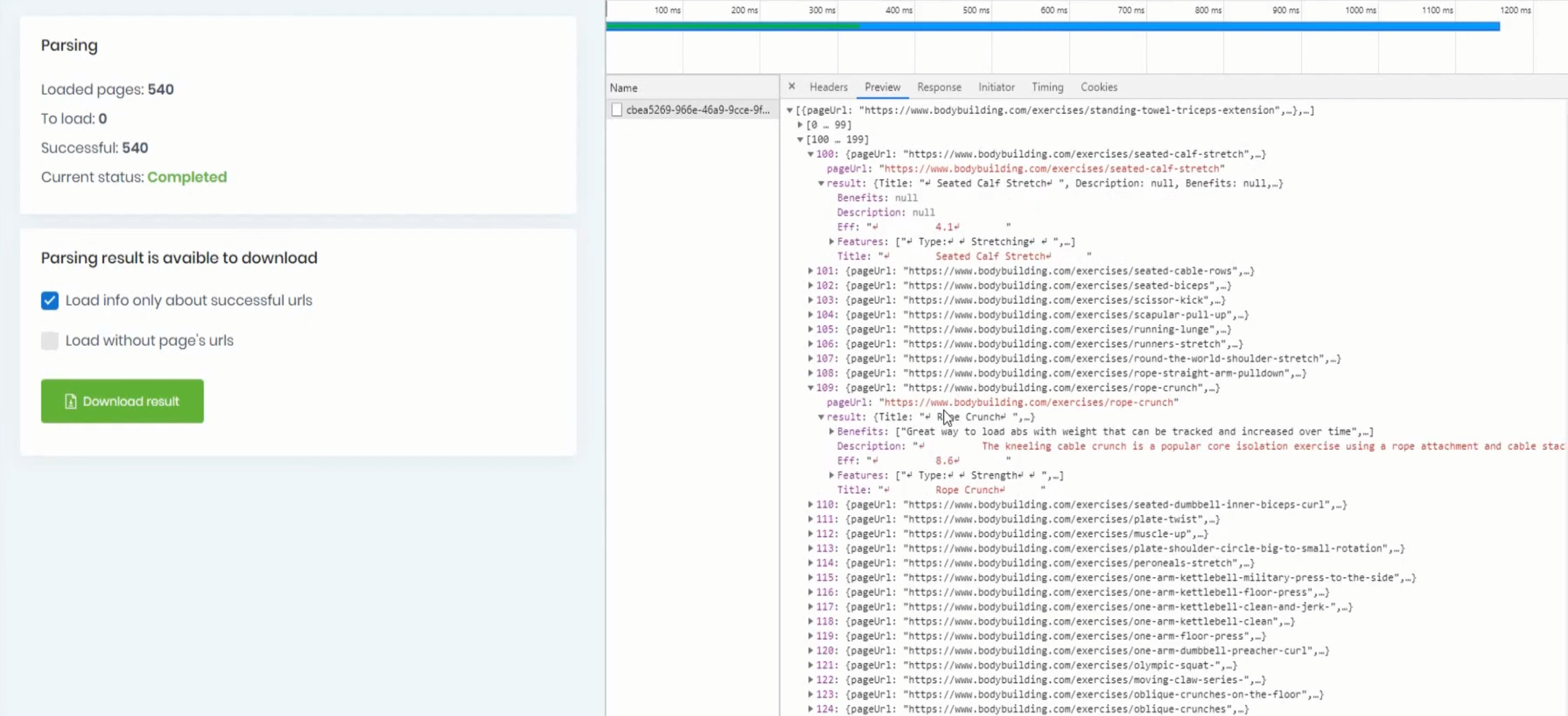

I asked my friend to help me build a pretty frontend for this application, and soon we got the application that builds crawling schema and runs it:

Step 1: Build the Schema

Step 2: Choose the Pages

Step 3: Run and Get Result

The main problems we encountered were:

The main problems we encountered were:

- Some pages required JavaScript to be rendered. Allowing JavaScript could break the window where the page was opened. After several iterations, I created web and desktop versions of the application. The web version allowed creating schemas for simple parsers, while the desktop version allowed enabling JavaScript and marking data.

- Page loading was often problematic. Many services help with JavaScript rendering and avoid crawler detection, but the project didn’t generate revenue, and using those services wasn't justified. I wrote several proxy rotators, but it was often difficult to determine if a proxy was working and whether a request with a proxy was successful. This was a problem I didn't know how to solve.

Rethinking The Concept

Then came a period with no free time, and I almost forgot about “web-crawler” for a year. I remembered it when I started developing another pet project. I still needed a tool to parse sites with JavaScript rendering and good protection against crawlers. I had a new idea: separate page loading from schema definition. Page loading could be difficult – solving captchas, rotating proxies – and it wasn't always possible to create a complete pipeline through the interface. I decided to sacrifice simplicity, abandon the interface, and create a C# library. I envisioned something like this:

var schema = new StaticCrawlingSchema() // or DynamicCrawlingSchema, depending on whether JS is needed to load the page

.HasProperty("title", Types.String, ".title")

.HasObjectProperty("user", ".user", userBuilder =>

{

userBuilder.HasProperty("name", Types.String, ".name")

.HasProperty("age", Types.Int, ".age")

.HasArrayProperty("dogs", ".dog", dogsBuilder =>

{

dogsBuilder.HasProperty("age", Types.Int, ".age")

.HasProperty("name", Types.String, ".name");

});

})The schema should be strongly typed, and the crawler should handle all type conversions automatically: integer fields should be parsed as Int32, dates as DateTime, etc. If a conversion isn’t straightforward, the user could use an overload that accepts a transform function. The schema should also allow complex actions like clicking or hovering before extracting an element's value.

First Library Implementation

The library was implemented close to the original plan. Users defined a class for the data they wanted to extract and a schema describing how to get the data from the page. They then chose a crawler that could work with that schema and started the processing. Initially, there were two implementations that could work with the schema: AngleSharp for static schemas and PuppeteerSharp for dynamic schemas.

Second Implementation

The problem with the first version was that dynamic and static schemas were almost incompatible. A common workflow was to start with a static schema and switch to dynamic if JavaScript rendering was needed. This required significant schema updates. I decided to unify the schema definition as much as possible, leading to the creation of a new builder class:

public class DocumentSchemaBuilder<TElement, TModel>

where TModel : class, ICrawlingModel

{

}with inheritors AngleSharpSchemaBuilder<TModel> and PuppeterSharpSchemaBuilder<TModel>. Each of them had its own implementation of:

interface ICrawlingAdapter<in TNode>

{

TDestination? MapValue<TDestination>(string? element);

Task<object?> GetValueAsync(TNode? element, Type destinationType);

Task<string?> GetInnerTextAsync(TNode? element);

Task<string?> GetAttributeTextAsync(TNode? element, string attributeName);

}to retrieve data from elements. This approach covered most cases related to schema incompatibility, and switching between schemas became easier (changes from static to dynamic usually didn't require schema modifications).

Scrap Anything

Once I needed to extract data from an XML file. XML is very similar to HTML, so I added minor improvements to the library to support parsing XML. The Document builder class was extended to support different selectors: HTML and XML.

public class DocumentSchemaBuilder<TElement, TSelector, TModel>

where TModel : class, ICrawlingModel

{

}I think the library architecture is flexible, and it will be straightforward to handle new conditions if they arise.

Conclusion

It was an interesting journey to create a library that helps (at least me) extract data from the web. I think combining crawling with AI could yield interesting results. For example, the crawling schema could be created automatically based on the page content. But that’s a story for future investigations.